This January and a good part of February, we have an opportunity to see six planets in the evening sky. For the most part, you will just need your eyes, a clear western horizon, and a cloudless sky. To take full advantage of this “planet parade,” you will want to grab a pair of binoculars or a telescope if handy.

What is a Planet Parade? Is it Rare?

Known colloquially as a “planet parade,” these planetary gatherings are not particularly rare. We had a planet parade in August 2024, though that one required an observer to get up just before sunrise to catch a glimpse. August 2025 will provide us with yet another early morning planet parade (unfortunately, Mars will sit that one out). This month, though, we just have to wait for the Sun to set to see Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. All but Uranus and Neptune are visible to the unaided eye, but you will only need a small telescope (or at least a good pair of steadied binoculars) and decently dark skies to catch sight of them.

You may hear specific dates given for when one should try to observe the planets; however, keep in mind that the planets won’t visible for a single date. In fact, if you have a somewhat clear western horizon you can still see all six planets through the second week of February. If you are privileged enough to have a completely clear western horizon so you can see down to nearly zero degrees altitude, it is even possible (though difficult) to catch these planets almost to the end of February.

When it comes to planet parades, it is not uncommon to hear “the planets are lining up.” This is somewhat misleading as it sounds like the planets are positioning themselves in a straight line in the solar system. This is not the case (and can never actually be the case). One could say that the planets are “in a line.” When you spot the four naked eye planets and figure out where the other two are located, you will see that they essentially follow a single line known as the ecliptic. There is nothing unusual about this, though. The planets all orbit in nearly the same plane around the equator of the Sun, deviating by a few degrees at most. Thus, they appear to all pass through the same part of the sky along with the Sun as it moves along the ecliptic. The Sun and planets all pass through the famous zodiac constellations, though the planets may slip a bit into adjacent constellations every now and then thanks that their slightly tilted orbits.

Tips For Observing Each of the Planets

Though Uranus and Neptune may not be much to look at in the telescope, it is still really cool to be able to actually see them, especially considering you are looking at objects billions of miles away. On the other hand, the four naked-eye planets each have some interesting features worthy of dragging out the telescope. Keep in mind, though, that three of the planets are placed well over in the lower western sky and will only visible for a short while after sunset. Timing is key, and the planets wait for no one.

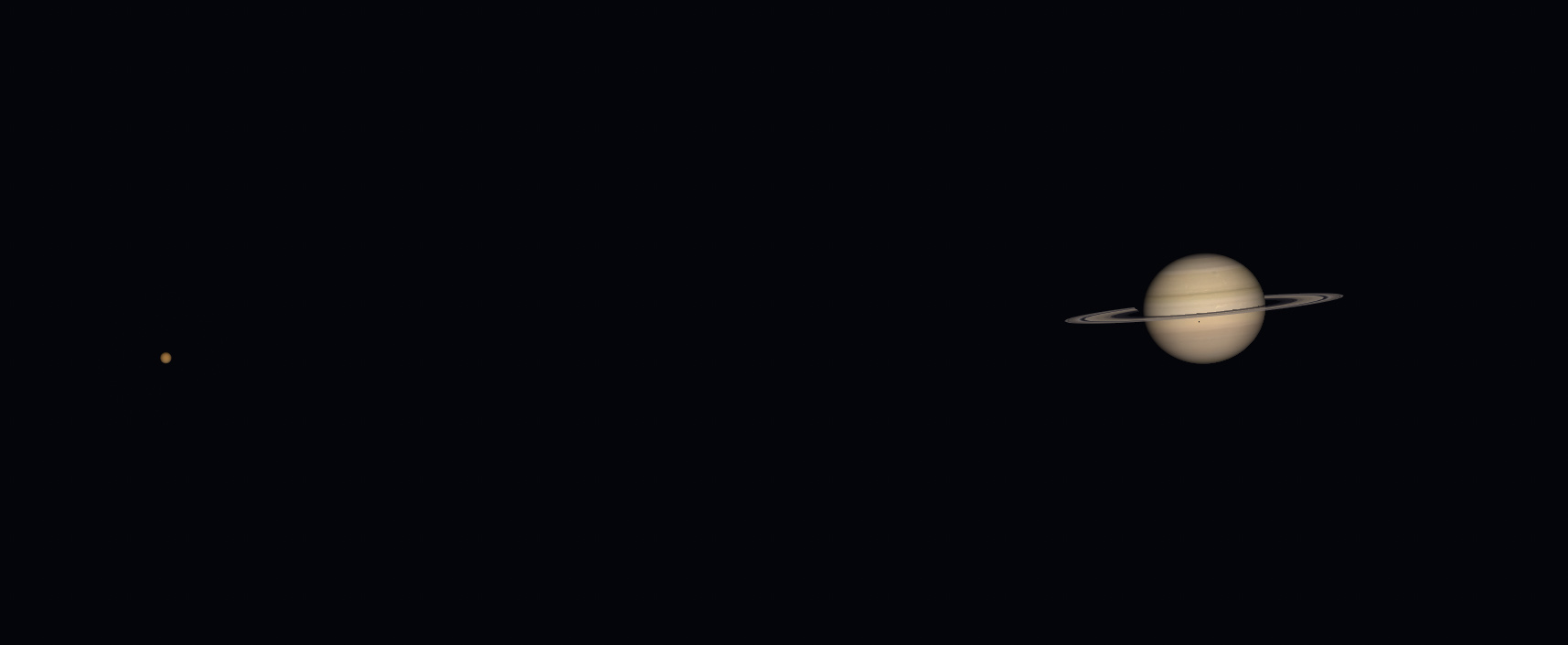

Saturn

The first planet to set is Saturn. It will still be bright enough to see with the naked eye, but you will need a telescope to get a view of the rings and its largest moon, Titan. Saturn’s rings will almost resemble a needle piercing the planet. In March of 2025, Earth will pass through Saturn’s ring plane, meaning there will be a few-day period wherein the rings will appear edge-on. Given that they are less than a mile thick and we are observing from nearly a billion miles away, they will be rendered invisible. Unfortunately, Saturn will be near its closest point to the Sun in our sky (solar conjunction) during this time, making it all but impossible to get a decent view. In November, however, we will have another chance to view Saturn when the rings are nearly edge-on. Conveniently, it will also have returned to the evening sky.

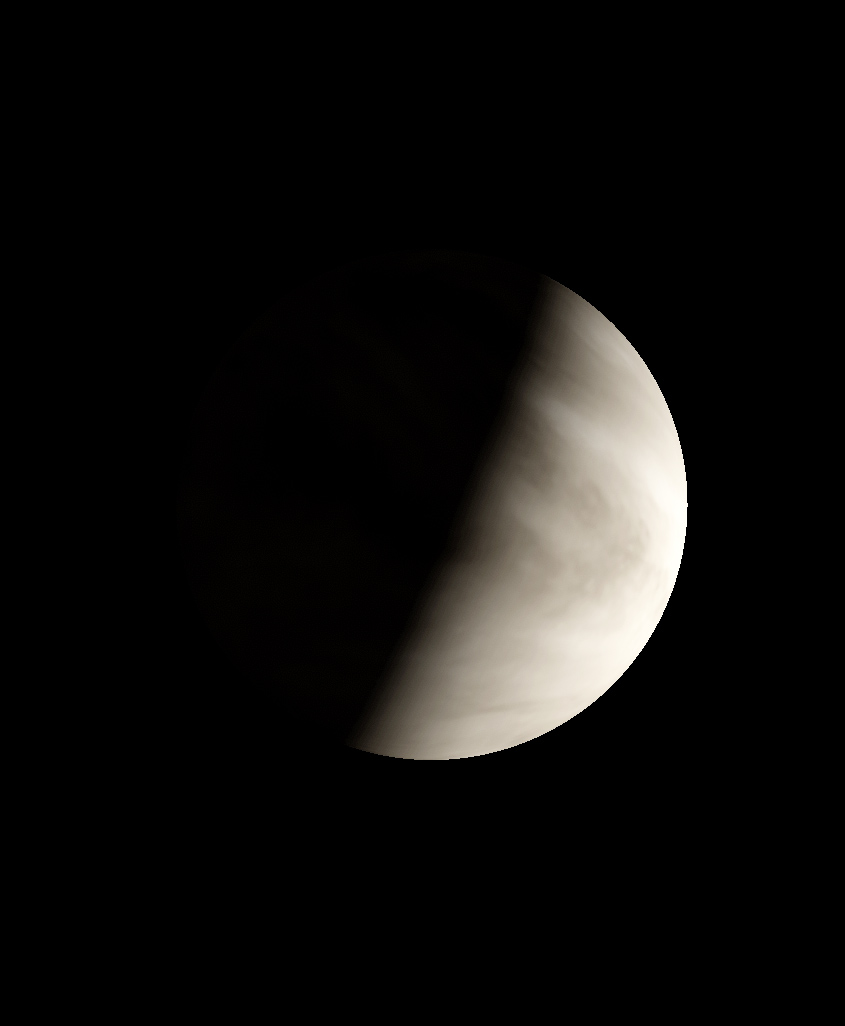

Venus

Venus has been putting on a show for several months now, gleaming brilliantly in the southwestern sky as the “Evening Star.” In the first half of January, it is the first of the six planets to set, but by the third week of the month its orbit brings it up higher than Saturn in the evening sky. On January 18, the two come within almost two degrees of one another. If you have a telescope, be sure to check out Venus. It now presents a lovely quarter phase that will become a crescent by the start of February as it catches up to us. Over the next few weeks as Venus draws closer, it will grow larger in the eyepiece of a telescope and the crescent will become narrower. Eventually, just a steadied pair of binoculars will show the crescent phase. It is a truly beautiful sight, especially when seen against the soft blue glow of dusk.

Neptune

The next target is the most challenging as it is the faintest — Neptune. At more than four light-hours away, it appears as a faint star in small telescopes. Moderately large instruments with decent magnification will help reveal the blue hue and spherical shape. It can be a challenge to find, especially when trying to distinguish it from the background stars. On February 1, the Moon and Venus try to help out. For some viewers, especially those on the eastern seaboard and even farther east, the Moon, Venus, and Neptune form a straight line for an hour or so with Neptune lying only about a lunar width from the Moon. In January, Neptune dips below the horizon just after Venus, setting earlier and earlier as time goes on.

Neptune will not move an appreciable amount over a couple of months, so the accompanying chart can be useful for finding it if the Moon cannot help.

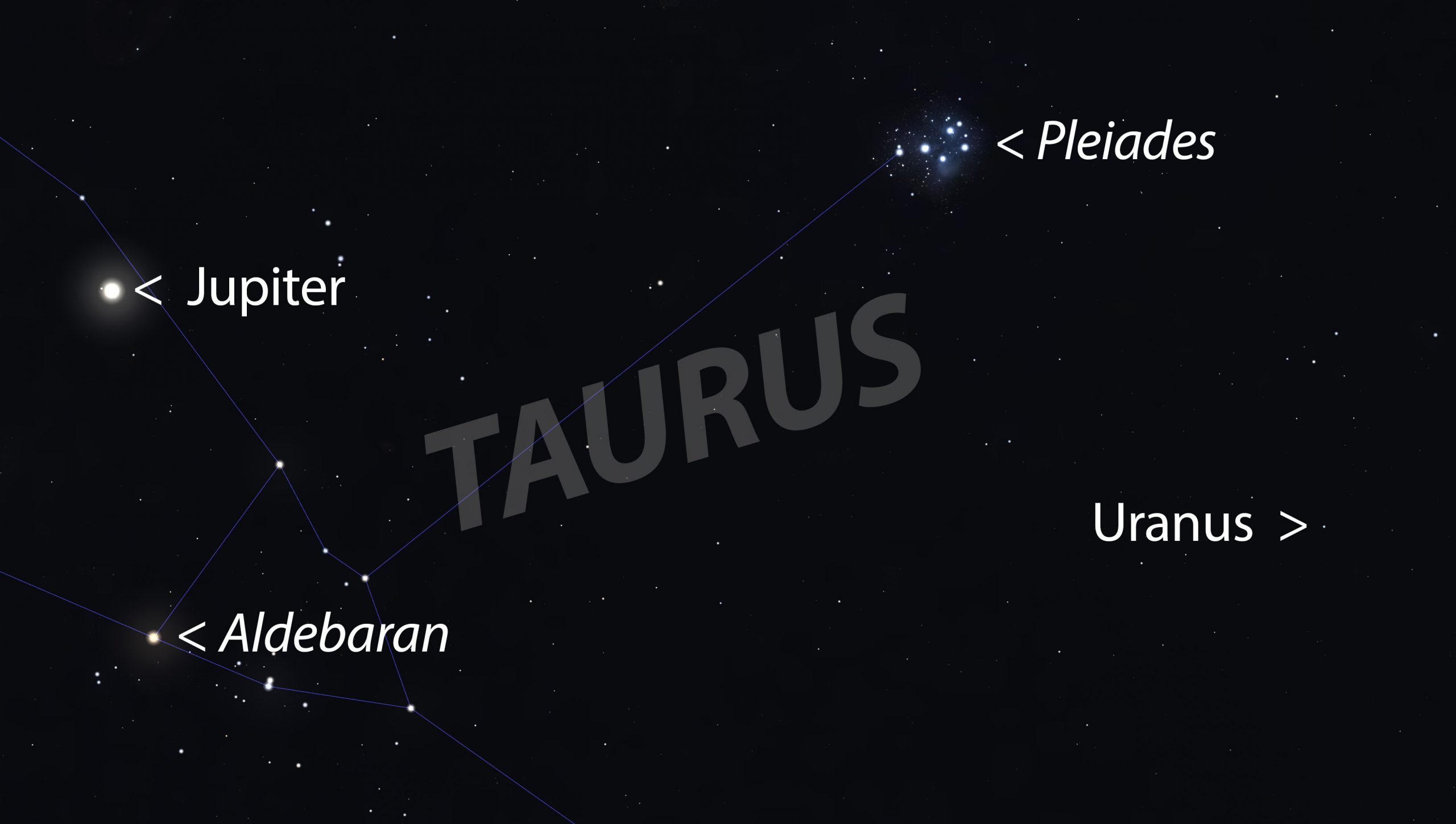

Uranus

Fourth on the list is Uranus. Though still somewhat difficult (but easier to locate than Neptune), it is bright enough to be seen in binoculars. The blue-green orb of the planet can be resolved with a small telescope and good magnification under calm seeing conditions. Still, one must find it first. It is not extremely close to any really bright stars this year; however, one can make use of some other markers as guides to the ringed world. If using binoculars (or the finder of a telescope), locate the bright star Aldebaran around 7pm local time, gradually scan directly to right, passing under the Pleiades, until you happen upon a moderately bright star. With moderate magnification, one can see that Uranus is not a point source like a star, providing confirmation of whether or not the observer has truly found it. The star chart below can allow one to “star hop” from Aldebaran to adjacent stars to find Uranus.

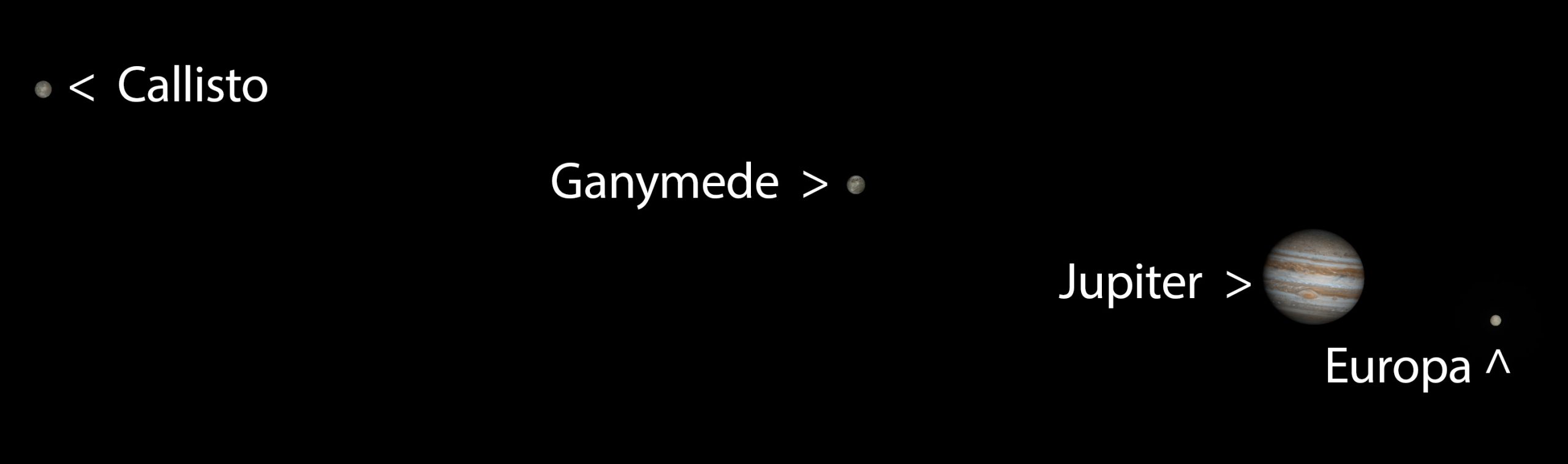

Jupiter

From here on, it is easy sailing as the final two planets are visible even under the glow of bright city lights. Jupiter and its four largest moons present a nice target for even small telescopes. Larger telescopes with a bit more resolving power may also pick up the infamous Great Red Spot if timing is right. Sky & Telescope magazine has an online calculator that will give users the transit time (time of passage across the middle of Jupiter) of the Great Red Spot, and one can usually see it well for roughly an hour before and after the listed transit time. Just make sure you note if times are Universal Time (UT) or local time.

Mars

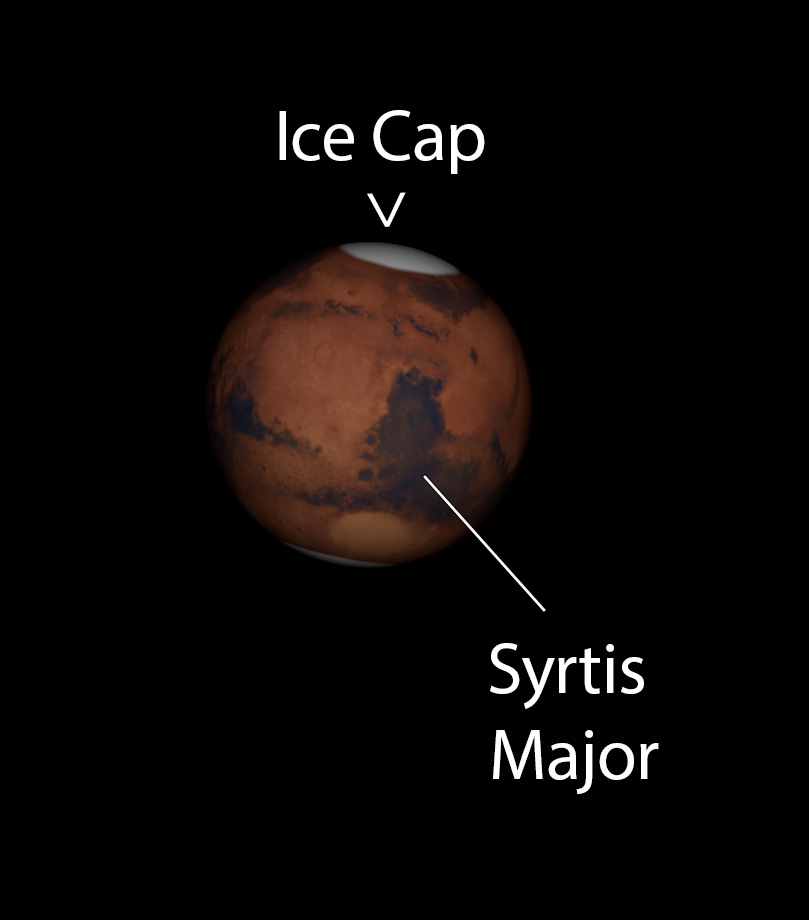

Finally, we reach the Red Planet, aka Mars. Mars reached opposition on January 12, meaning Earth came pretty much between it and the Sun. That is a key position because it means we will be at or near our closest position to it (making it appear largest in telescopes), and it will be visible all night. Mars has some interesting surface features including prominent white polar ice caps, reddish-orange soil, and dark rocky regions such as Syrtis Major. Mars does have two tiny moons; however, don’t expect to spy them through the eyepiece of a telescope. By themselves, they are very faint, and it is even more difficult to glimpse them with the bright glare of Mars nearby.

A Bonus!

Getting to see six planets in one evening is a thrill, but there is a bonus for those who really love a challenge. Mercury begins returning to the evening sky during the last week of February, appearing less than two degrees from Saturn on February 24th and 25th. Thus, it is possible to see seven planets in the span of a few hours one evening. The problem is that they are extremely low to the horizon by the time the glow of dusk fades enough to pick them out. It’s doable, but it will take a very clear horizon and likely at least a pair of binoculars.

If you want to really get technical and have even more bragging rights after catching sight of Mercury, then don’t forget to point your telescope or binoculars to a distant hill as well so that you can boast that you have seen ALL of the planets of the solar system in one evening (including Earth)! Good luck!